‘But you, Bethlehem Ephrathah,

though you are small among the clans of Judah,

out of you will come for me

one who will be ruler over Israel,

whose origins are from of old,

from ancient times.’

Therefore Israel will be abandoned

until the time when she who is in labour bears a son,

and the rest of his brothers return

to join the Israelites.

He will stand and shepherd his flock

in the strength of the Lord,

in the majesty of the name of the Lord his God.

And they will live securely, for then his greatness

will reach to the ends of the earth.

And he will be our peace.

Micah 5:2-5a

While most people would just think that Micah’s words are uplifting or powerful and some may see in them a prophecy, an anthropologist would look at the social impact of those words and some of the underlying socio-political assumptions of the prophet. In particular, I want to focus on one word that is often disregarded. In some translations it is even absent. That is the word “clan”. It is noticeable that Micah does not use the normal word for clan – mishpahah, but rather the somewhat archaic term ‘elef. This term has a lot of significance.

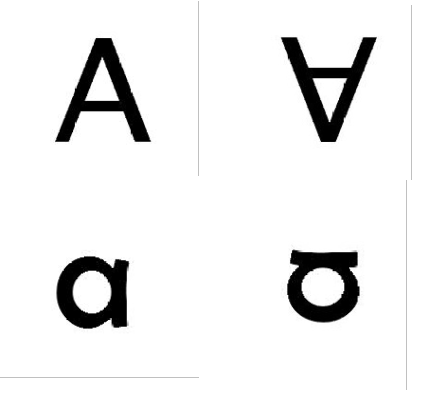

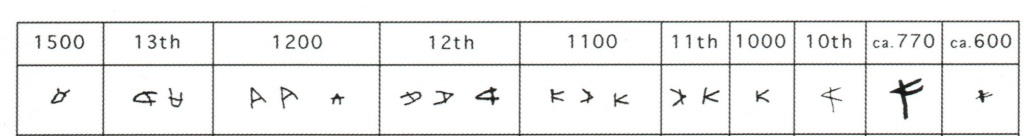

The first letter of the Hebrew alphabet is the letter ‘alef. Written in full it is the same as the term used here for clan: ‘elef. Both those terms come from the same root: ox.

The letter ‘alef initially developed from an Egyptian hieroglyph showing an ox. In the Sinai, where the first form of an alphabet was developed, the ox head became a bit more schematic. From there it became more abstract and turned in every which direction over time. By the sixth century it was difficult to see an ox head in the letter. It seems that the term for ox was also pronounced slightly differently from the letter by that time.

The Latin alphabet developed from the Hebrew alphabet via a few intermediaries. But still today we can see the ox shape in the present letter A. Just turn the capital letter A on its head and you’ve got the ox head; turn the lower case letter a on its side, and again you’ve got the ox head.

The modern Hebrew letter ‘alef doesn’t look anything like an ox head. That’s because during the Exile, a new Hebrew script was adopted that derived from Assyrian symbols. That also means that the Bible was re-written at one stage from the old Hebrew script to the new Hebrew-Assyrian script. Just in case you wonder, that’s the explanation why there is not that association between ox and the first letter of the alphabet in later Hebrew.

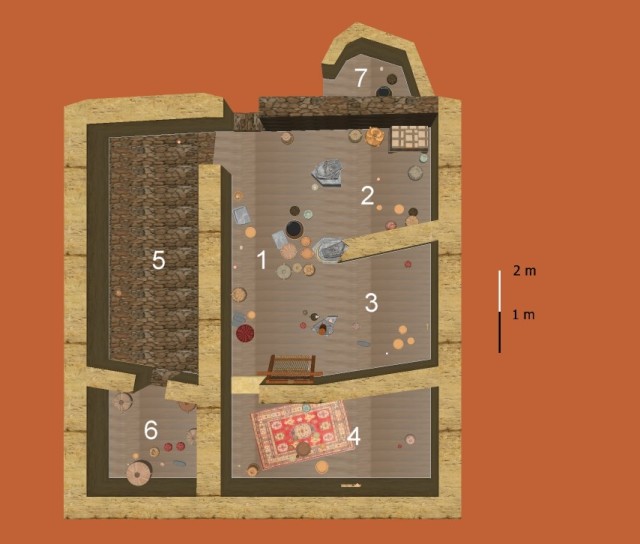

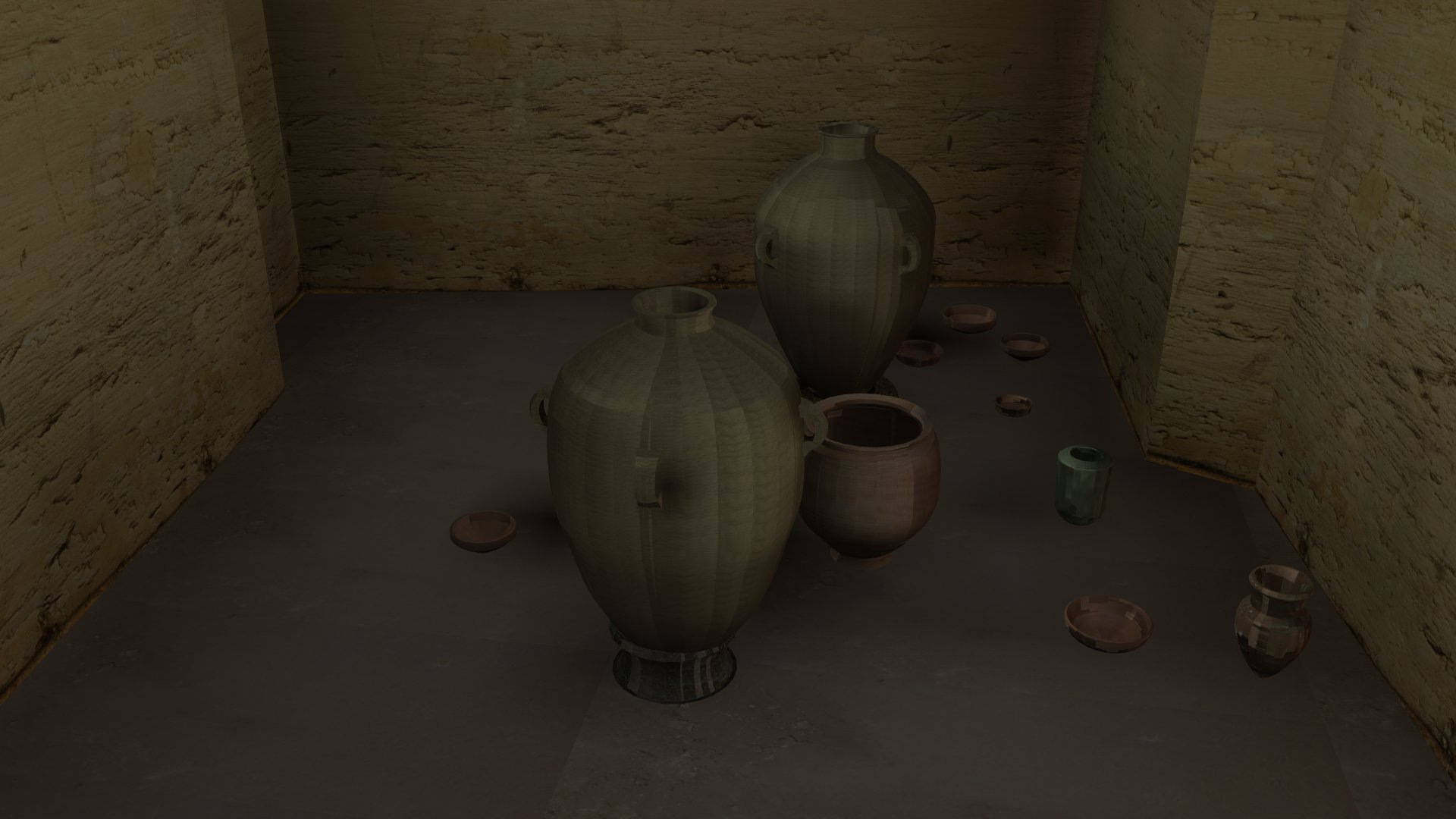

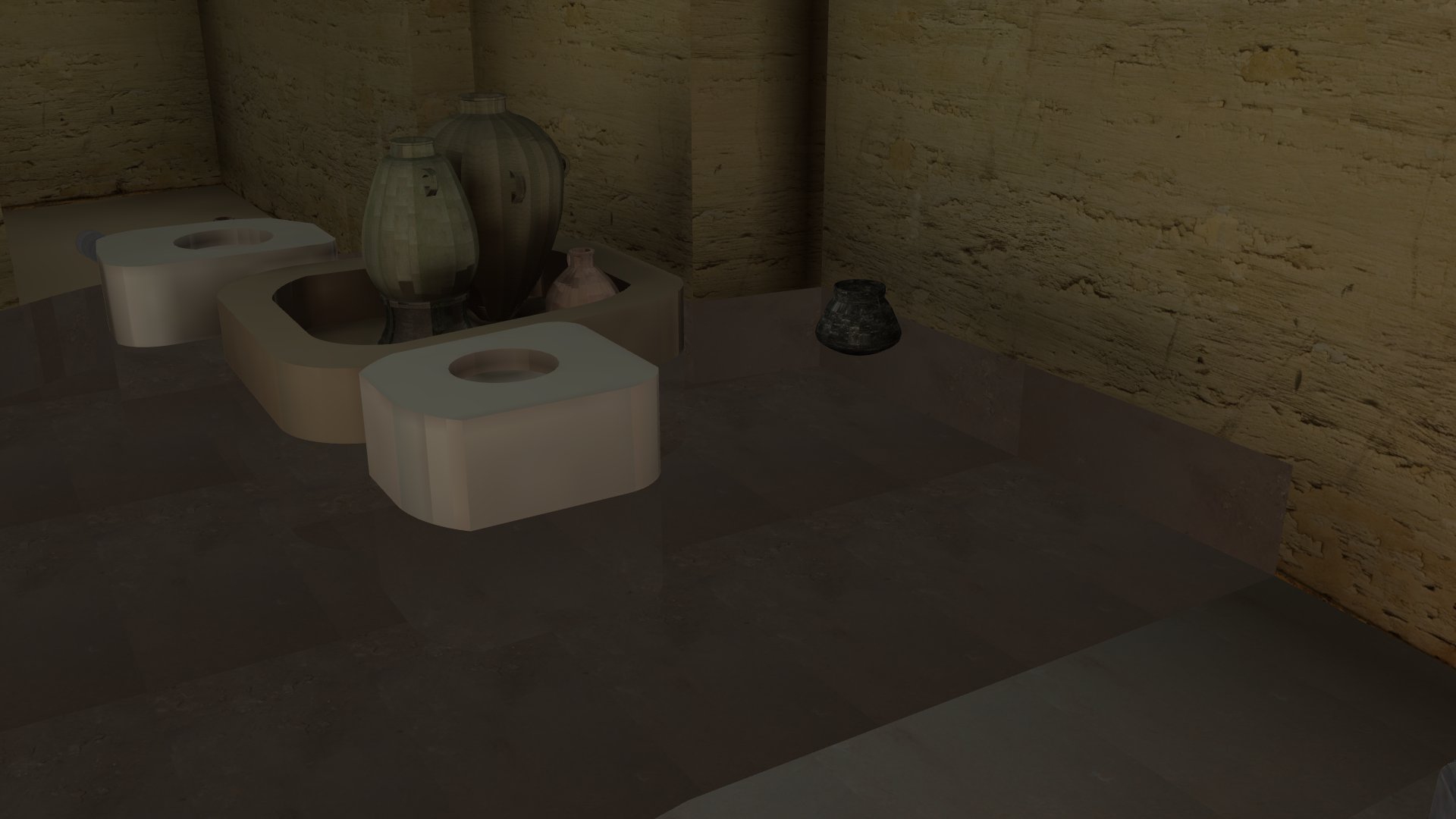

The term ‘elef also developed in other directions. Over time it took on the meaning of clan, that is the families that shared an ox together to plough. This clan was also the unit that fought together. In Ancient Israel the army did not consist of specialized units or people grouped by ability, but rather people from the same clan fought together. Those men knew each other and were familiar with each other. It had the unfortunate effect that if one fighting unit was wiped out, most of the men of a village were gone as well. During the time of the monarchy the army became more professionalised and the clan overall lost importance in the lives of the people.

However, the fighting unit in the army was still called ‘elef. Later such a unit consisted of a thousand men and the term ‘elef simply became the numeral “thousand”. The meaning of the word transitioned from ‘ox’ to ‘thousand’ in the timespan of a few hundred years. As an aside, several Biblical scholars suggest that the numbers of in the book of Numbers have been incorrectly understood, already by the editors of the Old Testament. These scholars suggest that the lists in Numbers are very old records that list the number of fighting units for each tribe. Such a unit would have consisted of approximately a dozen men. If you calculate it in that way there would have been just a few thousand people leaving Egypt during the Exodus, rather than around a million. That would certainly be in better accord with the archaeological record and take into account the development of the Hebrew language. However, I recognise that such a suggestion also has its problems.

That is a long detour to discuss the term ‘elef. But once we understand that, it becomes clear that Micah used an old term for clan, when he spoke these words. These was the kinship group that was bound together in agriculture and as representative and fighting unit, a group that held in peace and in war. It is the clan Ephratah, one of the clans of Bethlehem, out of which David and the house of David came. Why would Micah not have used the term “son of David” or similar that is used quite frequently in other books of the Bible? Probably because he was deliberately intentional in choosing the terminology. It seems that in Micah’s opinion things had gone wrong when David became a king like others, and even more so when the descendants of David took the throne, when Israel and Judah became institutionalised kingdoms. It’s clear that throughout the book Micah is the voice of the rural community that has become disillusioned with the urban elite, particularly the court. He is frequently referring to elders of the land as the seat of more legitimate authority and criticizing the acquisitive bureaucracy of Israel and Judah. But Micah is still setting hope in God and a ruler that would lead Israel out of its predicament. That ruler would not come from the compromised royal system. No, that ruler would come from the old clan of Bethlehem, would be a new David, a David that would restore the true Israel, not the corrupted by the current leadership structures.

Micah says that the rulers origins will be from of old. He wants to bypass the whole overblown and entitled administration and the corrupt royal house and have a ruler from the old established roots, the people who have not been compromised. That ruler would be a true shepherd, who cares for the people like a good shepherd cares for the flock. And he will bring them peace and flourishing.

We could contrast Micah’s attitude to the king’s administration with more positive views, such as is seen in some of the Psalms and to a certain extent in the historical books. The prophet Isaiah is more complex, essentially pleading for a return to faithfulness, rather than an overthrow of the current system.

The words of Micah are quoted directly in the Gospel of Matthew as a fulfilment of prophecy. However, Luke retells the meaning of Micah’s words more fully and subtly. In the nativity narrative, Luke repeatedly tells us that Joseph was of the line of David, and even though Joseph was not Jesus’ real father, Jesus was the one who was born in Bethlehem and the son of David. Luke also connects Jesus to Micah in a way that is probably not that obvious to us modern readers, but quite clear to those Jews who thought in terms of kinship. The key verses are in Luke 3:23-38:

23 Now Jesus himself was about thirty years old when he began his ministry. He was the son, so it was thought, of Joseph,

the son of Heli, 24 the son of Matthat,

the son of Levi, the son of Melki,

the son of Jannai, the son of Joseph,

……

the son of Zerubbabel, the son of Shealtiel,

the son of Neri, 28 the son of Melki,

the son of Addi, the son of Cosam,

the son of Elmadam, the son of Er,

29 the son of Joshua, the son of Eliezer,

the son of Jorim, the son of Matthat,

the son of Levi, 30 the son of Simeon,

the son of Judah, the son of Joseph,

the son of Jonam, the son of Eliakim,

31 the son of Melea, the son of Menna,

the son of Mattatha, the son of Nathan,

the son of David, 32 the son of Jesse,

the son of Obed, the son of Boaz,

the son of Salmon, the son of Nahshon,

….

the son of Noah, the son of Lamech,

37 the son of Methuselah, the son of Enoch,

the son of Jared, the son of Mahalalel,

the son of Kenan, 38 the son of Enosh,

the son of Seth, the son of Adam,

the son of God.

There’s a whole lot of theology behind that genealogy. And a whole lot of history and social commentary. For my purposes it is instructive to compare this list of names to the genealogy in the Gospel of Matthew. They are different and commentators have wondered for thousands of years why that is. In the Gospel of Matthew the genealogy runs through the line of the kings of Judah. Here in Luke it does not. Yes, there is King David in that list, but after that the lineage goes through people that were all not kings. Nathan, the son of David, was a brother of Solomon, but never king. In other words, the genealogy by-passes all the corrupt institution and goes back directly to David and therefore to Ephratah, the clan from Bethlehem. Jesus is the ruler over Israel, whose roots are from of old, from ancient times. Jesus is the new Adam, the one who is what humans should have been, if they would not have risen in rebellion against God.

Sinful humanity is contrasted with the holiness of God; corrupt kingdoms with the kingdom of God. The importance of kinship is also emphasized in the Gospel of Luke by the mention of Elizabeth, the kinswoman of Mary. The clan continues to be important in God’s salvation history, certainly more so than empires. That last point becomes very clear in Mary’s response, the Magnificat, which includes the lines:

“The LORD has brought down rulers from their thrones, but has lifted up the humble. He has filled the hungry with good things, but has sent the rich empty away.” Much could be said about the Magnificat, but if we look at it from an anthropological perspective, it is evidence that these were people who saw God at work in the fall and rise of states. Taking these things together, it is clear that the Bible contains strands that are clearly anti-establishment. The Bible forments a group that cannot conform fully to the order of this world. Yes, the Bible also exhorts to obedience, but overall it is quite critical of worldly power and certainly the control of empires. It is little wonder then that in Christianity, too, there has been a long tradition of resisting empire and what is perceived to be corrupt government and a hankering for a holier state of affairs.